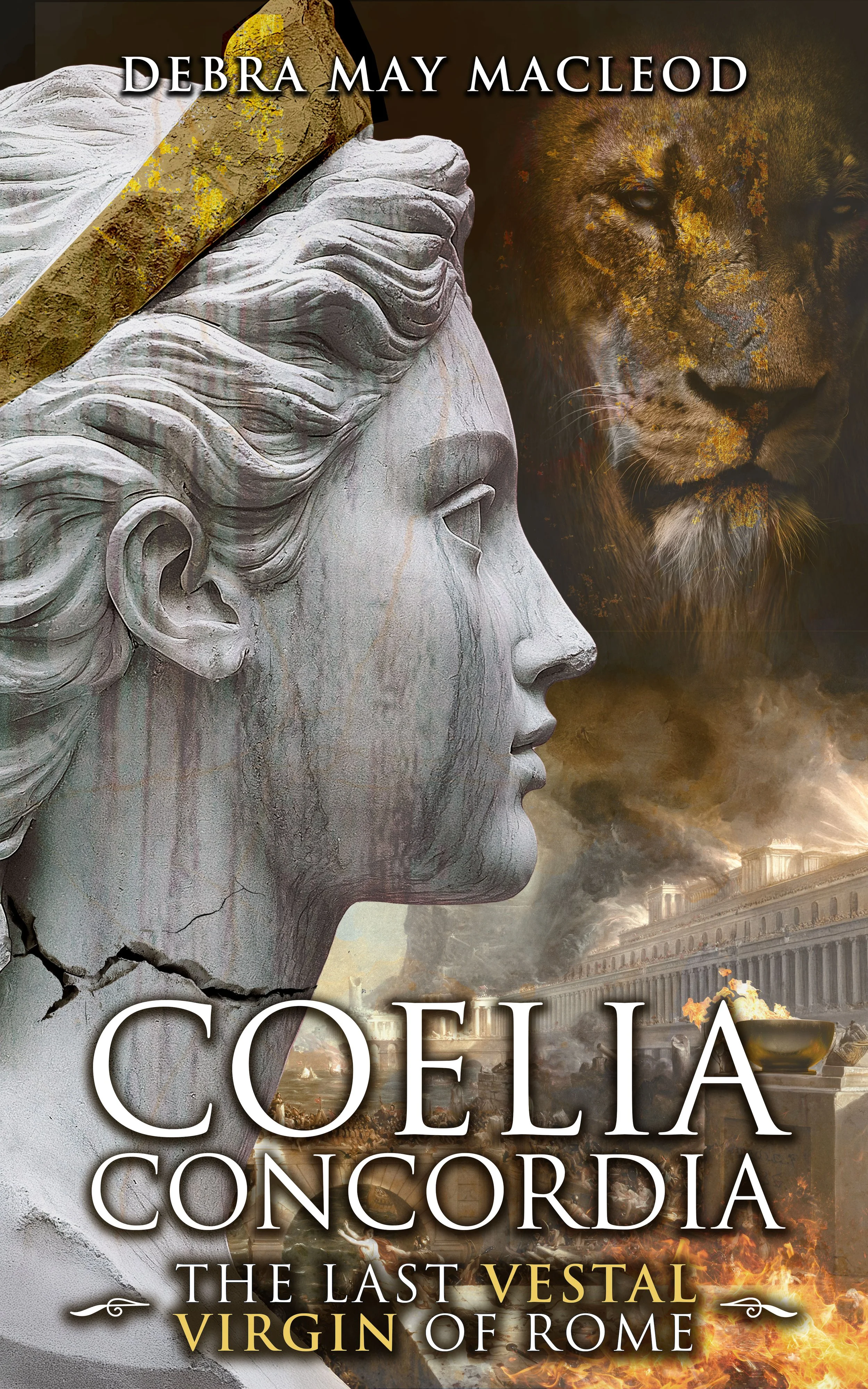

COELIA CONCORDIA

The Last Vestal Virgin of Rome

Read the Novel

The epic novel you must read by candlelight: immerse yourself in the world of ancient Rome, Vesta, and her privileged yet imperiled priestesses.

For over a thousand years, the esteemed priestesses of Vesta were tasked with keeping the goddess's Eternal Flame burning in her temple. As the guardians of Rome, the Vestal Virgins were revered, for as long as the fire was alive, the Eternal City would endure.

This is the violent, emotional story of Rome's last Vestal Virgin—Coelia Concordia—and her battle to save the sacred flame from an encroaching darkness.

It is also a story about an ancient prophecy, a curse fulfilled, and the relentless suppression of Rome's great gods and goddesses as seen through the eyes of those people who were losing everything—not just their gods and ancestral customs, but their freedoms—yet fought on and never lost hope. And all set against the backdrop of the biggest cultural shift in the history of Western civilization. Because the end of the Vestal Order heralded the fall of the Roman Empire.

Based on real events.

COELIA CONCORDIA is the seventh novel by Debra May Macleod, the author of six previous novels on the Vestal Virgins, books that chronicle the Vestal Order in Rome from its rise in the 8th century BCE to its banishment in the 4th century CE. While part of the larger world of the author's previous novels, it can be read and enjoyed as a standalone novel, or as an entry point into the captivating world of the Vestals.

About Coelia Concordia

Coelia Concordia was a real person. She served as a priestess of Vesta—a Vestal Virgin—in the latter half of the 4th century, also serving as the last chief Vestal, a position called Vestalis Maxima. She died in the early 5th century, not too long after the Vestal Order was officially disbanded by the Christian emperor Theodosius. We can only imagine how this important woman felt about the changes she saw happening in her world as her religion was outlawed and the sacred flame of Vesta, the one she and her sisters throughout the centuries had cared for, was extinguished. It is her life and that event—among many other events that took place during this world-changing period —that I have dramatized in my novel Coelia Concordia: The Last Vestal Virgin of Rome.

But here, let’s see what remains of Coelia Concordia today. Let’s begin with this illustration.

This is a more-or-less contemporary illustration of a marble statue and base found on the Esquiline Hill in Rome in the late 16th century (image taken from the Justi Lipsi de Vesta Vestalibus Syntagma). The statue was found headless and armless, as depicted in the illustration.

The inscription on the base allowed those who unearthed the statue to identify it as Coelia Concordia. The inscription indicates that the statue was dedicated to Coelia Concordia by Fabia Paulina, on account of the chief Vestal’s holiness in the worship of the divine and also because the Vestal had previously commissioned a statue of Fabia’s husband, an important man of the time, named Praetextatus.

The smaller accompanying illustration on the left depicts the vittae ribbons worn by Vestals.

The accompanying illustration on the right features the adornments around the chief Vestal’s neck and upper body, specifically a large jeweled medallion.

The Extant Statue of Coelia Concordia

“Extant” is just a fancy word meaning “surviving.” And when it comes to the statue of Coelia Concordia, there’s good news and bad. First, the good. Her statue survives. It has for many years been in the expert care of the Colonna Gallery in Rome. That gallery has been kind enough to provide me with some beautiful professional photographs. Let’s look at them… and as you do, you might be able to guess what the bad news is.

Photos provided by the Colonna Gallery, Rome

As you can see, the head… it wasn’t on the illustration, it isn’t Coelia Concordia, and one might say it isn’t particularly suited to the statue. (It’s actually a head of Pothos, a god of desire.) The same goes for the arms / hands and the implements in them—a flute and a theatrical mask. The clothing at the neck and upper body has also been reworked, and all traces of the Vestal vittae from the illustration are gone. In its current form, the statue is meant to represent a Muse.

The medallion has likely also been repositioned. The original iteration of the medallion would have boasted fine jewels, but if by some miracle they did indeed remain intact until the time of the illustration, they are long gone now.

Nonetheless, there is unmistakable similarity between this statue and the Vestal statues that currently stand in the ruins of the House of the Vestals in the Roman Forum, something that closes the distance between the centuries they were created. In fact, Coelia’s statue is remarkably similar to the statue of another Vestalis Maxima, below.

A Vestal statue from the House of the Vestals

The positioning of the arms, the presence of the vittae and the hint of a belly button below the fabric all resemble Coelia’s statue.

The presence of the holes in the marble also indicate that this statue, like Coelia Concordia’s, once boasted an ornate jeweled necklace and medallion or fibula.

Although the marble base of Coelia Concordia’s statue has been lost to time or vandalism or both, it probably looked fairly similar to the stone pedestals under the Vestal statues in the House of the Vestals (bases do not necessarily match the statues).

Vestal statues and bases from the House of the Vestals

Sadly, we’ll probably never know what Coelia’s face really looked like. Yet we can at least speculate as to how her medallion looked. Since the Vestals were wealthy aristocratic women, I think it is safe to assume that the medallion was gold. As for the jewels, it is my opinion that they were most likely either garnet or carnelian stone (both of which are red) and pearl. This red and white arrangement would complement the red and white arrangement of a Vestal’s infula headband, with red representing the sacred fire and white representing either the purity of the priestess or the priestess herself in her white customary clothing.

Using these assumptions, I had a jeweler recreate Coelia’s medallion, below.

Reproducing the Medallion of Coelia Concordia

Photo from author’s collection

Seeing the medallion in color, with the red and white gemstones against the gold surface, gives us just the smallest sense of how grand a Vestal truly was, and how striking the piece must have looked against her white clothing. The jewels are arranged in the shape of a so-called pagan cross.

You can read more about this process in “Recreating the Medallion of the Last Vestal Virgin,” or watch this video.

Coelia Concordia, in Silver

Coelia Concordia belonged to the ancient plebeian Roman gens Coelii. While she is not seen on any coinage, her ancestor Gaius Coelius Caldus—a statesman who lived during the time of republic and was a contemporary of Cicero—is found on coinage.

Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com

This is an image of Gaius Coelius Caldus on the obverse of a denarius from the mid-1st century, minted in Rome. On the reverse, there is a depiction of a type of ritual feast called the Epulum Jovis.

If you’ve read the novel, and if you like putting a face to the name, keep scrolling. Here, you’ll find some historical items and images that give us a glimpse of some of the other real-life characters in Coelia Concordia.

First, Symmachus: or more precisely, Quintus Aurelius Symmachus.

Who’s Who (for Real) in the Novel of Coelia Concordia

Detail of Symmachus in Ivory Diptych, Wikimedia Commons

This is an ivory panel (currently in the British Museum) that depicts the illustrious pagan senator ascending to the heavens under the watchful eyes of the sun god Helios (top right).

Symmachus is surrounded by signs of the zodiac. He moves toward men who, like him, are wearing togas. They are most likely his ancestors.

Monument to Symmachus, Wikimedia Commons

And here, we have a (funerary) marble statue base for Symmachus. The inscription lists the public offices he achieved during his career. The monument was dedicated by his son, Quintus Memmius Symmachus, to his “most excellent” father. This statue base is in the care of the Capitoline Museums.

While not a character per-se, this ancient Roman coin depicts the winged goddess that stood atop the famous Altar of Victory in the Senate House, the one that Symmachus and his fellow pagan Romans fought so hard to keep in the Curia according to ancient custom.

Bust of Emperor Gratian, By TimeTravelRome - Wikimedia Commons

Emperor Gratian… an important figure in the novel, of course, and for all the wrong reasons. Regardless, here is a marble bust of the young emperor, whose full name in Latin is Flavius Gratianius. This bust is located in the Rhineland State Museum in Trier, Germany.

Moving on to a very well-known emperor, Theodosius I. Like Gratian, he was no friend to our Vestals.

Going from father to son, next is Emperor Honorius, the son of Theodosius. This depiction is from an ivory diptych. If you zoom in on the emperor’s face, you’ll quickly relate to the way I have described him in the novel (and perhaps you too can see the family resemblance).

Before we take a break from emperors, consider this depiction of Emperor Valentinian II, looking very imperial indeed, at the Istanbul Archaeological Museum in Turkey.

Statue of Emperor Valentinian II - Wikimedia Commons

This next ivory panel is a real treat, as it depicts three central characters in the novel.

On the right-hand panel is General Stilicho himself.

On the left-hand panel is his wife Serena, and beside her, their son Eucherius. This panel is located in the Monza cathedral outside of Milan.

First, here is what is believed to be a contemporary depiction (meaning it was done around the same time that he lived) of Ambrosius, the bishop of Mediolanum (Milan), known today as St. Ambrose.

This likely represents the bishop’s true appearance.

Yet it is isn’t just real priestesses, senators, soldiers and emperors we can still get a glimpse of. Bishops are here, too.

Next is a statue of St. Ambrose of Milan currently in the Duomo Museum in Milan. It is how the church prefers to portray the bishop.

The scourge he wields symbolizes the punishment he inflicts upon heretics. It also symbolizes the church’s authority in all matters and over all people, even the emperor.

Next is Innocentius, the bishop of Rome, known today as Pope Innocent I.

While not a contemporary depiction, we can nonetheless reflect upon the bishop’s visage in this mosaic medallion. It is located in St. Paul’s Basilica Outside the Walls.

Ancient coins are a great resource when it comes to getting a glimpse into the past. We’re going to rely on them to show us the faces of two important and like-minded emperors of the later Roman Empire who feature in the novel.

Gold coin of Julian, by Classical Numismatic Group - Wikimedia Commons

Here is the determined face of Emperor Julian.

Julian was the last openly pagan emperor of Rome. Often called Julian the Apostate by the church (since he converted from Christianity to paganism), he is also called Julian the Philosopher for his wisdom and his interest in higher thought.

The next very similar gold coin depicts Emperor Eugenius… this is the face of a man with a lot on his mind.

Gold coin of Eugenius, by Classical Numismatic Group - Wikimedia Commons

Additional People & Points of Interest

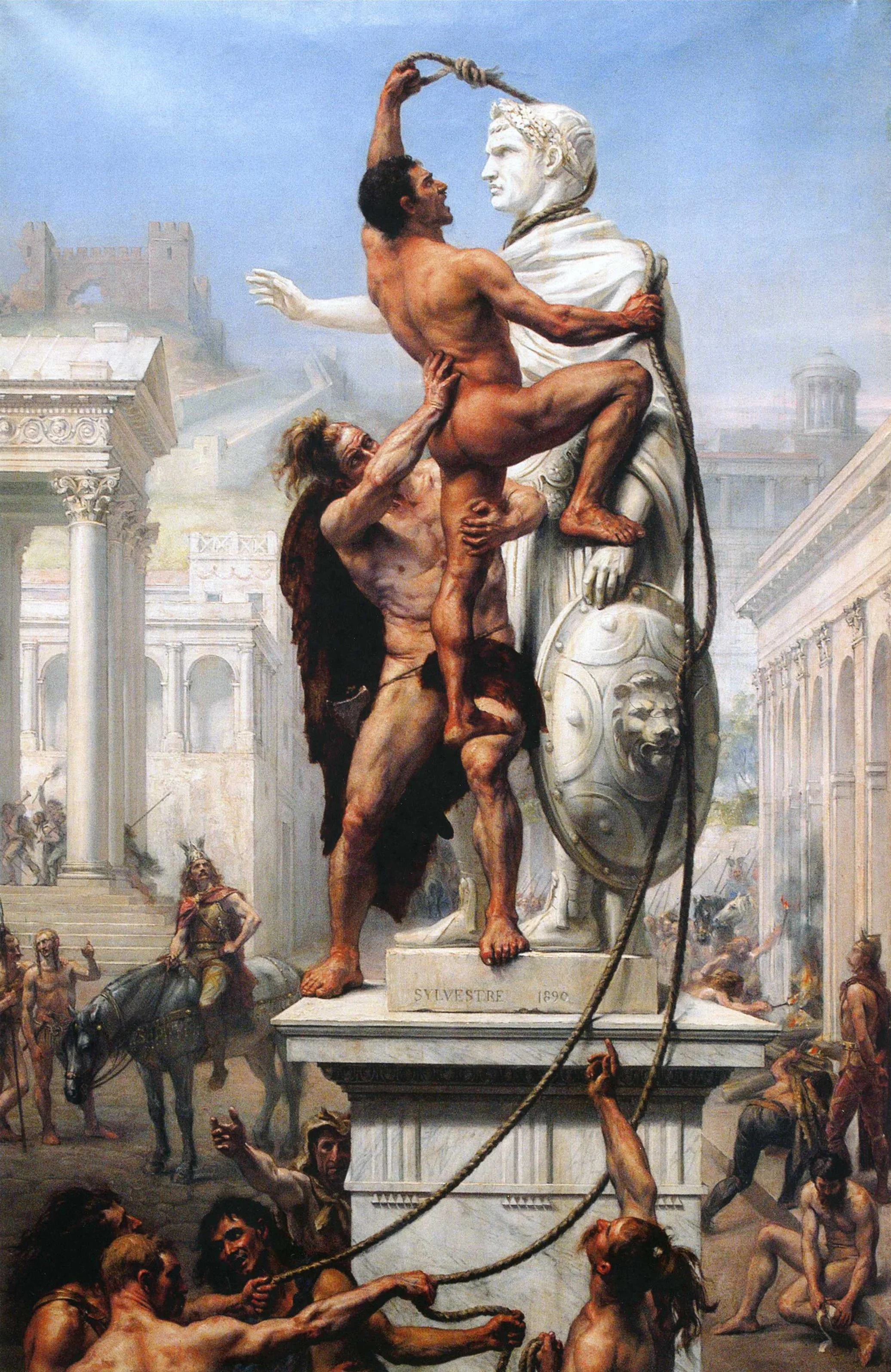

If you look at the chap sitting on a horse in the lower left of this painting, you’ll see him - Alaric, king of the Visigoths. He is the man who led the invasion and sack of Rome in 410 CE.

This unhappy scene, obviously, depicts the invaders toppling a statue of a Roman emperor who holds a shield boasting one of the enduring symbols of the city, a lion.

This page would not be complete with including an image of Caesar Augustus, the first emperor of Rome. He was the adopted son and heir of Julius Caesar.

Augustus as Pontifex Maximus, Picryl

While there are many extant statues and busts of Augustus (including the most famous of all, the Prima Porta), this statue - which shows the emperor dressed in the role of the Pontifex Maximus - has always been my personal favorite.

We can imagine the emperor - and those emperors who came after him - dressed like this as he performed the sacred rites with the Vestalis Maxima and other priests.

This statue is located in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme.

The Cumaean Sibyl & Entrance to Her Cave

The Cumaean Sibyl has long been a figure of mystery and awe.

Here, I’ve included a fresco detail of the Sibyl as imagined and painted by Castagno in the 15th century. In her left hand she holds the famous prophecies. This fresco is in the Uffizi Gallery.

Beside the Sibyl is a photo of the actual opening to the Cave of the Sibyl in Cumae (the archaeological park).