How Nuns Replaced Rome’s Great Pagan Priestesses

As ancient Rome’s powerful and revered all-female priesthood, the Vestal Virgins certainly had little in common with the religious order of women that would rise as they were suppressed... namely nuns. And here, we’ll take a look at how it all happened.

The dedication of a novice Vestal Virgin

Illustration of a nun

If you’ve read or seen any of my other content, you know who the Vestal Virgins were and what they meant to Rome. But I’ll do a quick recap in case you’re new, because you can’t really understand the scope or impact of their forcible disbandment without knowing some of the background.

Now, ancient Rome – right from the time of its founding, through the centuries of the kingdom, the republic, and the empire – was polytheistic – there were many gods and goddesses. The most important were the 12 dii consentes, which more or less mirrored the 12 Greek Olympian gods, but there were also many, many more gods.

These were the earliest gods of our Western culture and civilization, and if you’re of a certain heritage, these were the gods of your own ancestors... who, by the way, were free to honor whatever gods they wanted to thanks to ancient Rome’s long-standing policy of religious tolerance. As long as you kept the peace, respected the customs of Rome and paid your taxes, you were good. Only disruptive religions, or those who sought to undermine other religions, ran into problems.

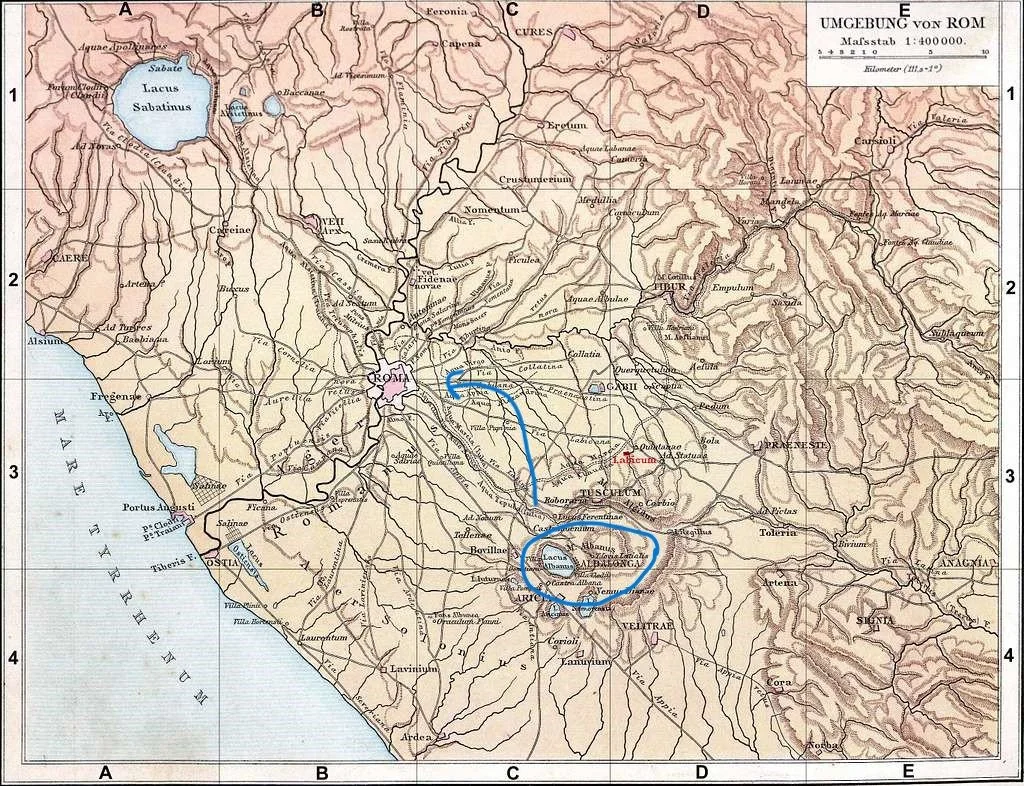

Because ancient Rome recognized the natural balance in the divine, they loved their goddesses as much as their gods, and respected their priestesses as much as their priests. And the greatest of these priestesses were the Vestal Virgins. This was an all-female priesthood that actually pre-dated the founding of Rome. We know the Vestal Order was in Alba Longa, for example, which is commonly thought of as Rome’s mother city.

The location of ancient Alba Longa, circled in blue

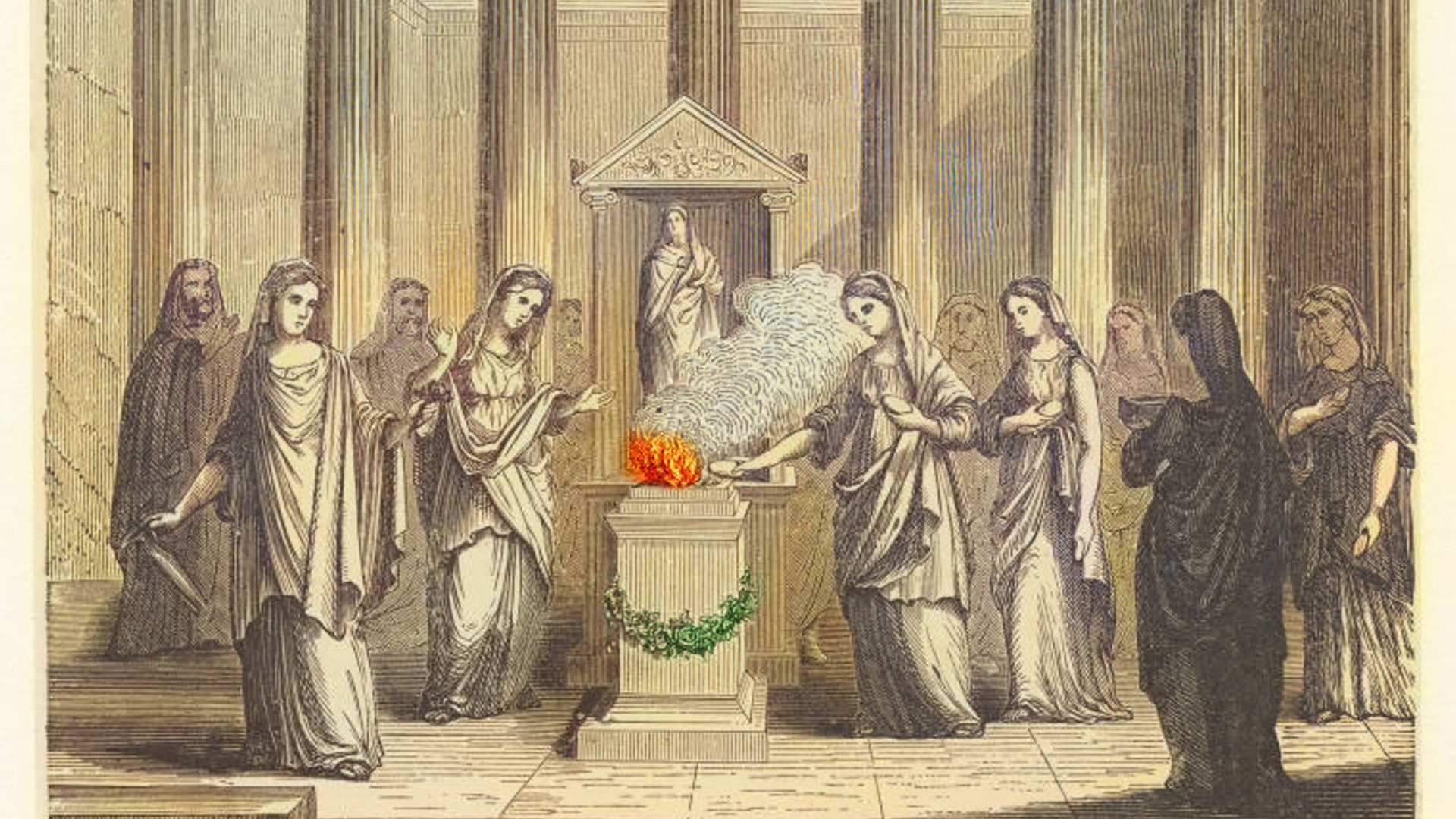

An illustration of Vestals around the sacred fire in the temple

These priestesses honored the powerful goddess Vesta, goddess of the home and hearthfire. She was worshipped in every home, but also in her temple in the heart of the Roman Forum. The priestesses lived right next door to the temple in the very fancy House of the Vestals – think underfloor heating, marble walls, private apartments, a courtyard with decorative pools and so on. You can visit the ruins of both the temple and the house today.

The primary duty of the Vestal Virgins was to keep the goddess’s Eternal Flame burning in the temple, because it was believed that if this sacred fire went out, Rome would lose the favor of the gods and suffer terrible catastrophes like plague, famine, war and invasion.

Because Vesta was a virgin goddess, her priestesses were expected to be virgins too in order to better commune with her. They therefore took a vow of chastity, dedicating thirty years of their life to the sacred flame and the Vestal order.

The Destruction of Empire, by Thomas Cole

Illustration of a Vestal Virgin

But as much as some people – even today - try to cast the Vestals as dried up spinsters, that just wasn’t the case. Vestals were selected as children from the best families in Rome. They lived very full, important and interesting lives.

They were very pampered too, eating the finest foods and receiving the highest quality of medical care. They had front-row seating in the Colosseum and moved in the highest social circles.

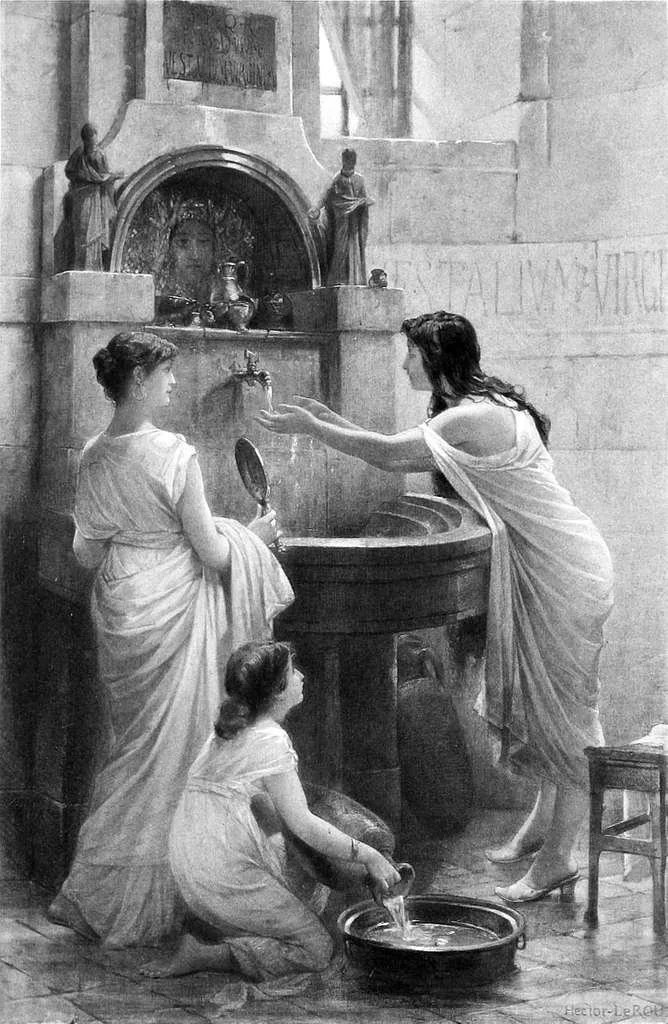

Young Vestals gathering holy water

The Vestal Virgins enjoying front-row seating in the Colosseum

And after their tenure was over - typically in their later 30’s - they had the choice to remain with the order or leave religious life and public duty. If chose to leave, they took their money, jewelry, real estate, business enterprises and well-connected friendships with them. Life was then wide open for them. They could stay in Rome or retire to a countryside villa. They could marry if they wanted to.

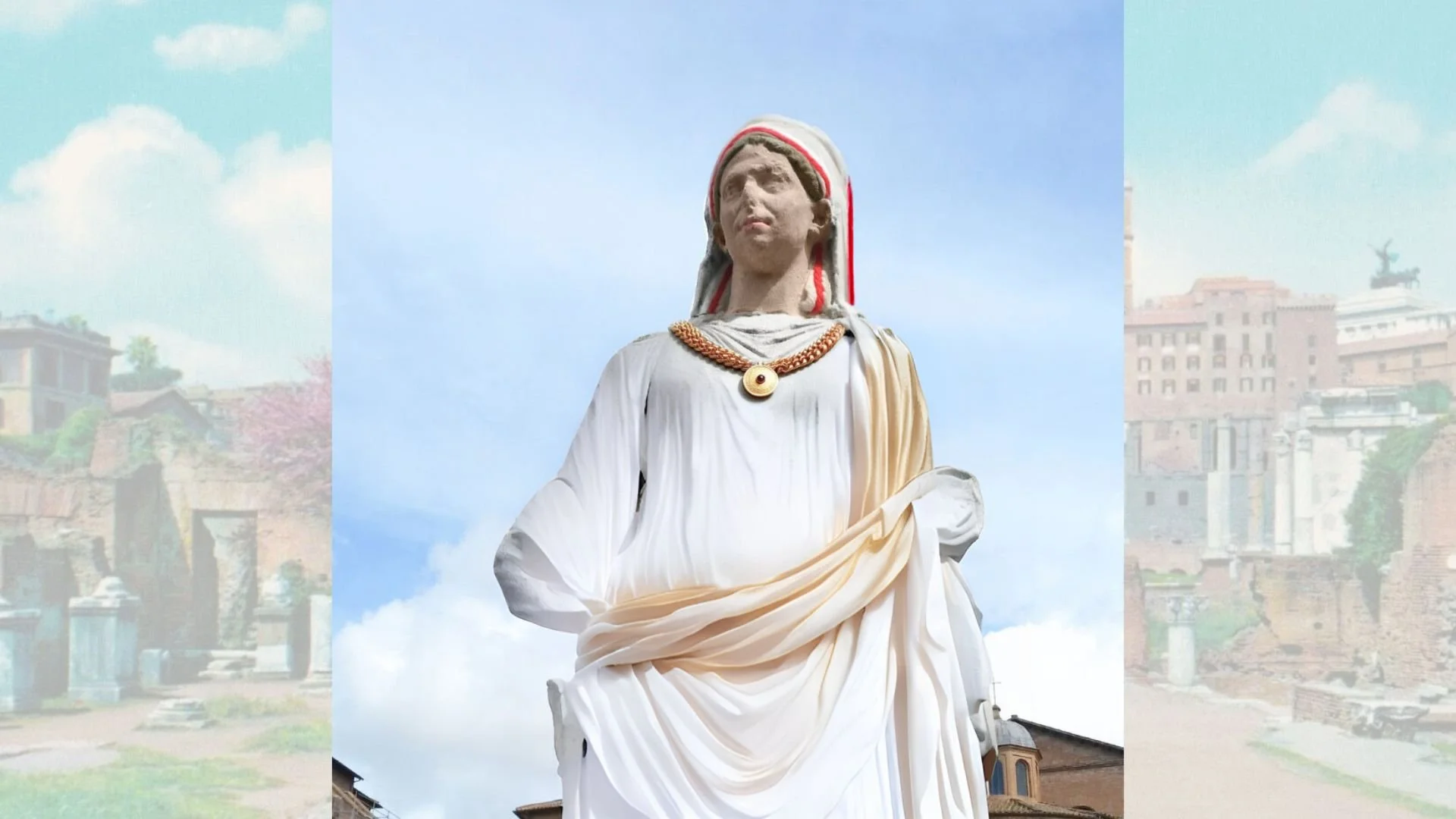

So the Vestals truly were Rome’s great priestesses, and the greatest among them was the Vestalis Maxima, which literally translates to the greatest or the highest Vestal. This was the chief Vestal. The head of the order. The high priestess. And do you know who she answered to? Essentially only one person - the Pontifex Maximus or chief priest of Rome who, at the time of the empire, was the emperor himself. So everybody answered to him.

Photo of a statue of a Vestalis Maxima, edited to show how it may have looked with white clothing and jewelry (as ancient statues were often adorned)

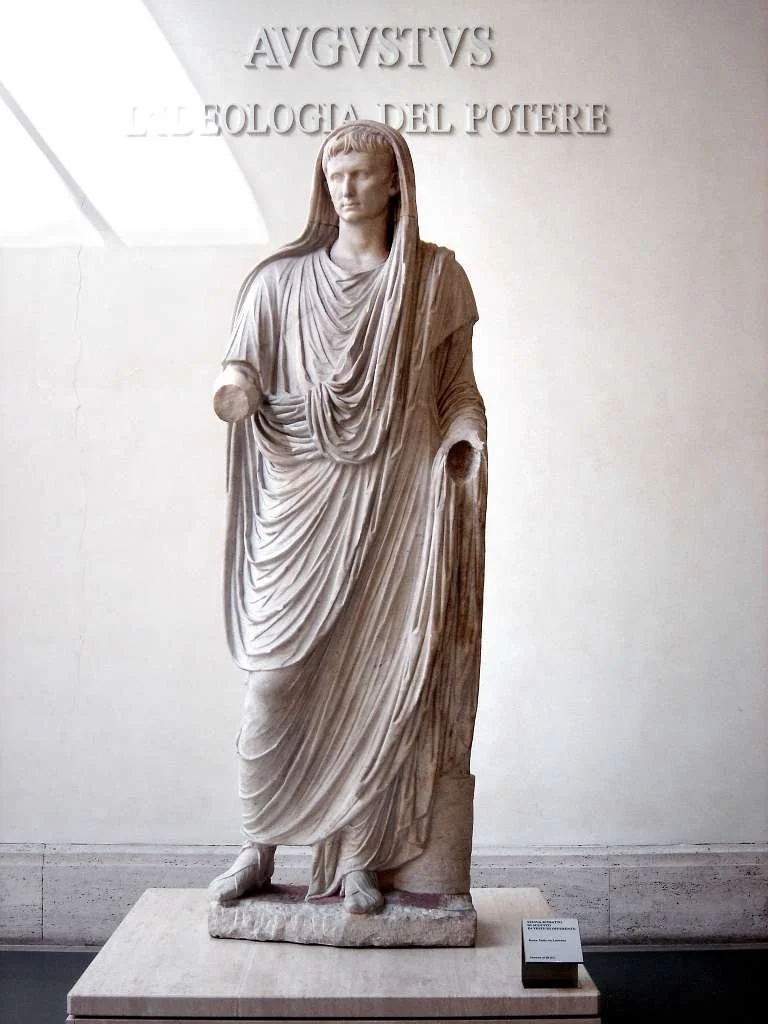

A statue of Emperor Augustus as Pontifex Maximus

While we know the names of a number of women who served in this illustrious capacity, I want to talk here about the Vestalis Maxima named Coelia Concordia. And honestly, few women in history have ever had to endure as much trash talk, misrepresentation and hypocritical moralizing as poor Coelia.

Born into a respected yet plebeian family, Coelia Concordia rose through the ranks of the Vestal order – completing her novice training and her years performing temple duties – to become the chief priestess in the later part of the 4th century CE… probably one of the worst times in history to serve in the role.

That’s because tectonic changes were happening in Rome at this time. While many if not most Romans were still pagan / polytheistic and honoring the traditional gods of Rome, a dogmatically monotheistic religion from the middle east - called Christianity - had been adopted by some key players in Rome, including the emperors. They and other Christians did not honor the customary or ancestral gods of Rome, but instead honored a prophet from Judea.

A scene showing the goddess Minerva and the god Neptune bringing a dispute to Jupiter

Rembrandt’s oil study of Christ

Unfortunately for Coelia Concordia, the timing of her advancement to the status of Vestalis Maxima happened at right around the same time that the Emperor Theodosius made Christianity (and specifically Nicene Christianity) the official state religion. We also start to see increasing harsh anti-pagan laws around this time.

That spirit of religious freedom that had always existed in Rome was rapidly disappearing as Christians sought to ensure that their god, and specifically the one interpretation of their god which they had only recently agreed upon, was the only god. Everything else was heathen superstition.

Now, for a while, these anti-pagan laws seem to have been honored more in the breach than the observance. The fact was, there were many important pagans in Rome. Pagans held high and crucial positions in the military and senate, and many wielded incredible wealth and influence. The emperor needed these people for the army and government, especially in the Western Empire, to function. That was especially so since many Christians declined military service.

The Roman Army

Cicero speaks in the Senate

So who knows what might have happened? Maybe despite the laws, Rome could have retained some of its traditional religious coexistence, at least in practice. But some people wouldn’t have it, and one of them was a Christian bishop by the name of Ambrosius.

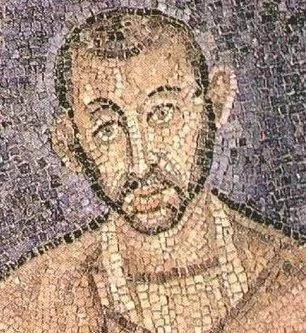

Ambrosius – you might know him today as St. Ambrose - didn’t actually begin his career as a member of the clergy. He started out as a politician, and didn’t even bother to get baptized until he was unexpectedly appointed the bishop of Milan in the 370’s. Nevertheless, he knows an opportunity when he sees one. He quickly goes hard-core early Catholic and starts leading the charge against paganism. Indeed, it’s hard to point to anyone who is more religiously intolerant during this time.

And the Vestal Virgins? They are smack in the middle of his crosshairs.

Because not only were the Vestals respected and very independent pagan women, but they served one of Rome’s greatest goddesses as consecrated virgins. And that is something that Ambrose absolutely had to put an end to. It’s no mystery why, either. It’s because the ancient order of the Vestal Virgins was direct competition for the order of Christian virgins – basically early nuns - that his own sister was part of.

The Vestal Virgins, keeping the sacred fire going and performing religious rituals

Nuns playing the piano and singing

Indeed, Ambrose had a lot to say about virginity, specifically female virginity. He even wrote a book about it - one that instructed girls how to be good Christian virgins - called Concerning Virginity. And of course, if he’s going to build up these Christian virgins, he has to tear down the Vestal Virgins. And here’s where the trash talk comes in.

A common depiction of Ambrose. The book represents his writings, while the whip on his desk represents his fight to quash paganism, including the Vestal Virgins.

A mosaic showing Ambrose’s real visage

Now, I must remind you of just how respected the Vestals had been to this point in Rome’s long history and how integral they were to Rome’s identity and to the state. Rome’s founder, Romulus, was born of the Vestal Virgin Rhea Silvia and the war god Mars.

The Vestal Virgins once saved Julius Caesar’s life by granting him sanctuary in the House of the Vestals. He later had Vesta minted on his coins. The great emperor Augustus bragged about supporting the Vestal Order, and images of the Vestals were included on his great monuments. The emperor Vespasian relied on the Vestals and gave them great liberty. The Vestals were Rome’s heart and soul.

Statue of Rhea Silvia with her sons

The Vesta aureus of Julius Caesar

Illustration of a seated Vestal Virgin

But now comes along this politician-turned-churchman who is determined to quash the Vestals and replace them with an order of religious women that he deems more suitable – and by that I mean more voiceless, more impoverished, less important, and of course serving his god. To do it, he basically launches a campaign to strip the Vestal Virgins not just of their status - that isn’t far enough - but also of their dignity.

In his writings, he slanders and mocks the Vestal Order. You can feel his contempt for these women leap off the page. He calls them immoral and unchaste. He ridicules their fixed 30-year tenure, saying that whatever lust they’re forced to suppress as young women, because of their vows, they’ll only unleash as old women. He knows that idea and image – an older woman being sexual – is easily mocked, so he leans into the shame and indignity of that.

He disparages the lifestyle and high status of the Vestals, too: the fine clothing and the fancy food, and how they have special privileges like riding in chariots. He doesn’t believe they deserve all the pomp.

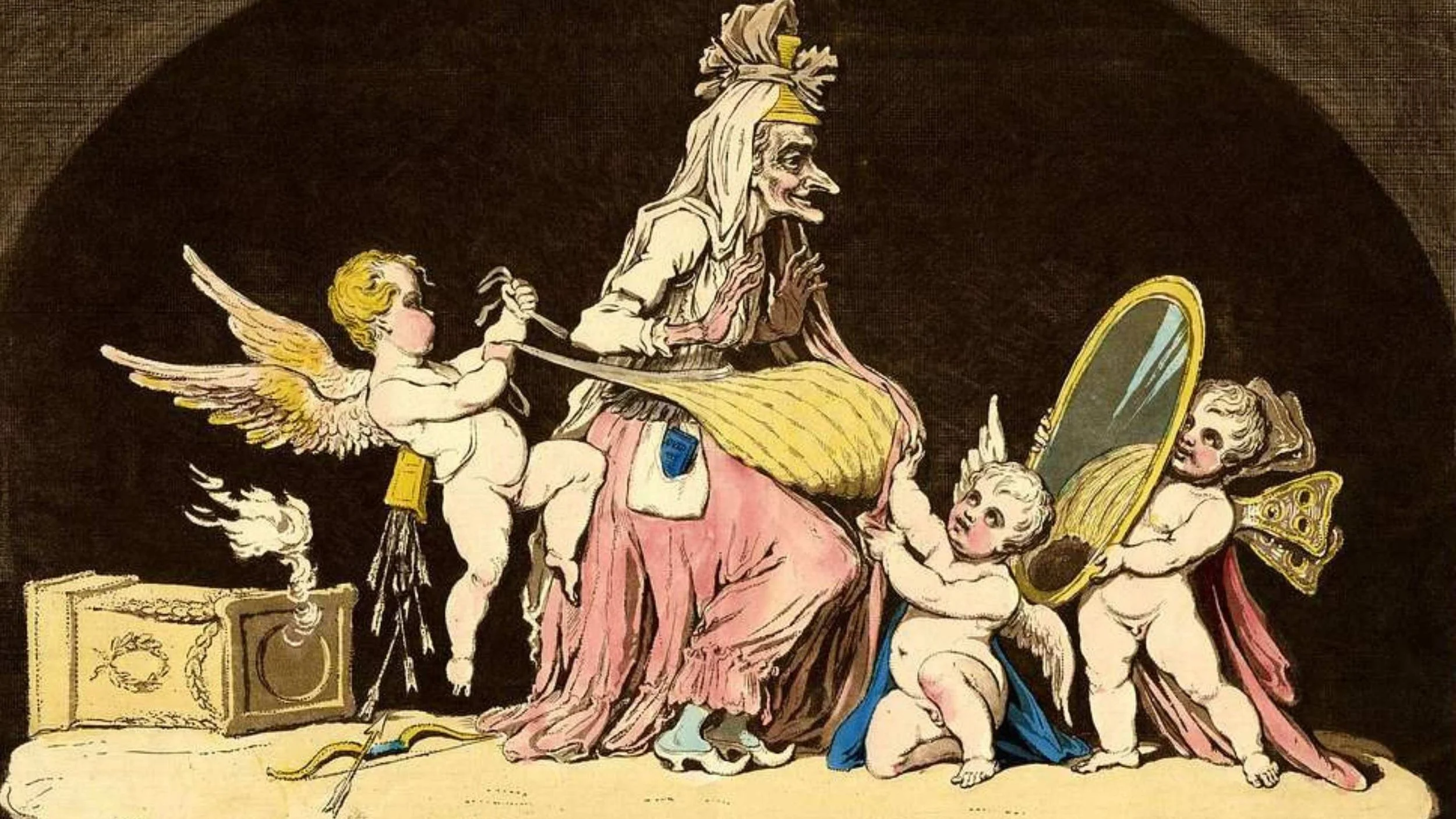

A political cartoon exploiting the image of an old Vestal (note the overturned altar) trying to look desirable

A scene depicting the respect shown to passing Vestals in ancient Rome

In contrast, he praises the Christian virgins, who are content to live and serve their god (and male clergy) in poverty, while the Vestals are paid a healthy stipend by the state.

And it’s this stipend, this payment, that he really despises. He perverts its purpose and insinuates that the Vestals are prostitutes who selling their virginity for a price. According to him, the Vestals are unchaste, wanton, dishonorable, greedy, and, ultimately, a bunch of dried-up old hornbags.

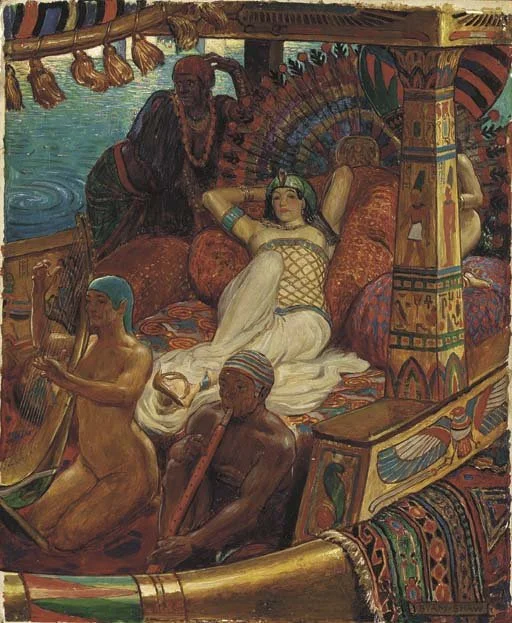

Because in the past, just as now, that’s how you bring down powerful women. By name-calling, ridiculing their age and sexuality, and of course comparing them to the type of woman that conforms to your ideology. Octavian’s propaganda machine did it to Cleopatra, spreading lies about her sexuality and contrasting her behavior with that of the noble Roman matron. Ambrose did it to the Vestal Virgins. And we’re still doing it to powerful women today.

A fresco from a brothel in Pompeii

Cleopatra depicted in a typically sexualized way

So Ambrose attacks the Vestals from all angles. He has to. He has to convince the Christian virgins that they are morally and religiously superior. And he has to do this relentlessly, because paganism is still alive and well at this point - it’s the natural state of things in Rome – and he can’t have the Vestal Virgins competing with his virgins. He can’t have their goddess – any goddess for that matter - competing with his god.

So he goes on the offensive and attacks the Vestal Order. And as the high priestess, it’s Coelia Concordia who bears the brunt.

Yet from what little remains of her legacy today, we can get a sense of how she might have handled all of this.

First, we know that she had a strong will and a mind of her own. She was willing to trust her own judgment and exercise her authority as Vestalis Maxima, even butting heads with the Pontifex Maximus of the day, a highly respected and important pagan senator named Symmachus.

I think we can also get a sense of her personality by examining what remains of her statue. And you can see it below: this is a statue of Coelia Concordia, Rome’s last great priestess - but what you must know is that the head isn’t her. That is not the face of Coelia Concordia. Those are not her arms or her implements either.

This statue was actually found on the Esquiline Hill in the 16th century, but the head and arms had either been knocked off or broken off. After it was recovered it was reworked to resemble a muse, which is why we see this mask and flute. We also see this head: it’s actually the head of Pothos, a god of sexual longing.

And if you compare the head on Coelia’s statue to this actual statue of Pothos, you can see the resemblance.

Statue of Coelia Concordia, the last Vestalis Maxima of ancient Rome

Statue of the god of sexual longing, Pothos

Whether whoever did this knew what they were doing, or whether it was just a matter of using whatever head was available – which was a common practice – we’ll never know.

Nonetheless, a couple things stand out to me about this statue. First, there’s a certain posture which is very confident but also very feminine. We can see the curves of her body, even her belly button. It’s quite similar to the statues we see of previous Vestals, including those that you can see today in the ruins of the House of the Vestals.

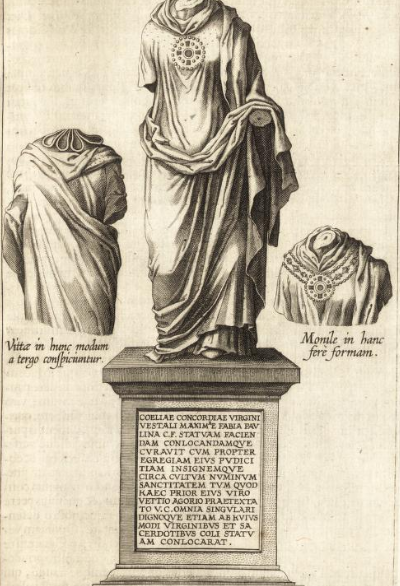

And although they’re not part of the statue anymore, if we turn to an illustration (see below) that was made of her statue shortly after it was excavated, and before it was reworked, we can see the ribbons that were part of her Vestal headdress. So she was very proudly displaying her status here.

There’s also that very large medallion that she’s wearing. It was undoubtedly gold and embellished with very expensive jewels.

When I first stumbled upon the below illustration – when I was doing my research for my historical fiction novel about Coelia Concordia – I was really taken with this medallion, and I actually had a jeweler recreate it. I’ve also included an image of how it likely looked in real life: red and white gemstones, with red representing the sacred fire and white representing the purity of the Vestals, all arranged in a pagan cross formation.

Illustration showing how Coelia Concordia’ statue was found

The recreated medallion that Coelia Concordia is wearing

Obviously it’s a very showy piece, and combined with Coelia’s posture, her Vestal attire, and the glimpse we have into her personality, I think it’s safe to say that this Vestal Virgin endured Ambrose’s insults and his slanders with the very dignity that he was so desperately trying to rob her of. In fact, I’ve often wondered whether the confidence and opulence of this statue, especially this very large medallion, was something of a statement to him and to those like him who were trying hard to shut down the Vestal Order.

In any case, the bishop’s campaign against paganism and against the Vestal Order in particular paid off in 394 CE when Theodosius issued the Imperial order that the sacred fire in the temple be extinguished.

It is worth stressing, however, that this did not happen without a fight, both on the battlefield and on the floor of the Senate. That pagan senator I mentioned earlier, Symmachus, he and others pleaded with the emperor to grant Romans the freedom to honor the gods of their own land and their own ancestors.

But it was not to be. By that time, the law had been weaponized against the pagans, and bishops held too much sway over the emperors.

So the gods of Rome were banished in their own land. But it didn’t stop there. Because once you banish or bury something, you need to figure out a way to stop people from digging it up. The law is one way to stop it, and the Imperial edicts criminalizing paganism were severe and relentless.

Arrogation is another way. That’s when you claim something - like an achievement or a cultural practice – as your own, when it isn’t. It’s easy to see with nuns. The style of headdress and veil worn by nuns are obviously taken from the Vestal Virgins. Just as novice Vestals had their hair ceremoniously cropped for the veil, so do novice nuns have their hair cropped. The Vestals actually had a fairly beautiful tradition of hanging the long locks of their hair on a tree, called the Capillata (hairy) tree.

Just like the Vestal Virgins used to wear the pagan cross around their necks, the nuns wore Christian crosses.

A close up of Coelia Concordia’s pagan cross medallion, as illustrated and recreated

A nun wearing a cross and wearing a headdress reminiscent of a Vestal Virgin’s headdress

But the similarities are only surface level. Sure, the nuns lived in convents that were reminiscent of the House of the Vestals, but where the Vestal’s residence was extravagant and full of servants, cloistered convents were pretty plain and the nuns did all the work. Not only did the nuns clean the churches, they cooked and cleaned for themselves, and eventually cooked and cleaned for the male clergy too.

I can assure you that no Vestal Virgin ever labored over a hot oven to make dinner for the male priests, or stayed behind to sweep the kitchen floor while the priests retired to the couches to have a drink and discuss important religious business.

That’s because the Vestal Order was an integral part of Rome’s religious college, and Vestals were entrusted with performing all kinds of religious rites. The Vestalis Maxima, in particular, was a very powerful woman religiously and socially. On the other hand, Christianity was a male-dominated religion where women were expressly forbidden from teaching men or holding significant, or truly meaningful, religious authority.

For example, consider the sacred wafers that that Vestals both made and used for centuries in various religious rites, both public and within the temple. The nuns continued to make these - they became the communion wafers of the Catholic church; however, only male priests were allowed to use them in religious ritual.

Vestal Virgins bring the sacred wafers to Vesta’s fire and prepare to perform a religious rite

Illustration of a priest holding up a sacred wafer in ritual while a nun watches in the background

Of course, the church arrogated many other things from the pagan religions, far too many to cover in this article. I will mention the virgin Mary, though, who was intended to replace virgin goddesses like Vesta, but certainly not just Vesta.

Below is an image of the powerful and beautiful Egyptian goddess Isis with her son Horus on her lap.

This mother-and-child scene is very obviously the model for the conventional image of Mary and Jesus.

The Egyptian goddess Isis, with her son Horus on her lap, nursing

Mary, with her son Jesus on her lap, nursing

But again, there are fundamental differences in the Christian religion that remove power and agency from female figures. While deities like Vesta, Juno and Isis and many others are powerful goddesses in their own right, that is not so with Mary. Mary is often depicted as a teenage girl, and she has no power of her own, only that which comes to her from her divine male child.

In any case, Ambrose ultimately had his way. He was able to get rid of the Vestal Virgins and replace them with an order of religious women that was more agreeable to him and to the church. And the way he did it – by misrepresenting the Vestals’ service, by disparaging their sexuality – certainly didn’t do women any favors.

Moreover, suppressing religious freedom by criminalizing other faiths certainly didn’t do the Western world any favors as it moved into the Dark Ages. And yes, regardless of how hard apologists try to erase this term, the Dark Ages they were, especially when compared to the freedom of religion, thought, assembly, ideas, and scientific inquiry that existed in earlier times. And I haven’t even touched on the whole burning-heretics-at-the-stake horrorfest. There is no doubt that the early church’s iron-fisted theocracy, and its particular ideas of the supernatural, made the world of the middle ages a dark and dangerous place for many people.

A painting of people burning in hell

Image depicting book burning

Yet as much as I’m ragging on Ambrose here, it wasn’t just him or the other male bishops who slandered the Vestal Order or worked to quash religious freedoms. There were many women at their side, helping to make it happen. The net result was to reduce the status of women in religious life while simultaneously robbing the Western world of the comfort and beauty and dignity of Rome’s great goddesses, all while marching toward a darkness.

But here’s the thing about something called an Eternal Flame. It doesn’t really ever go out. Neither does the force and the pull of custom. I think that’s why we’re seeing such a resurgence these days of paganism, in various places and in its many forms. Many people are turning back to the gods of their ancestors, and many are just exploring to see what feels right to them. And if you feel a sense of reverence or comfort when you look into the flame of a candle, maybe you’re seeing a flicker of Vesta yourself.

In any case, I hope you’ve enjoyed this article. If you’d like to learn more about the amazing Vestalis Maxima Coelia Concordia, visit the Coelia Concordia page here at All Things Vesta. Thank you for reading.